BBC Monitoring & BBC News

AFP

AFPTwo years ago, Sudan was thrown into disarray when its army and a powerful paramilitary group began a vicious struggle for power.

The war, which continues to this day, has claimed more than 150,000 lives. And in what the United Nations has called the world’s largest humanitarian crisis, about 12 million people have been forced to flee their homes.

There is evidence of genocide in the western region of Darfur, where residents say they have been targeted by fighters based on their ethnicity.

As of March the army has recaptured the presidential palace in the centre of the capital, Khartoum – a key victory which it hopes will mark a turning point in the conflict.

Here is what you need to know.

Where is Sudan?

Sudan is in north-east Africa and is one of the largest countries on the continent, covering 1.9 million sq km (734,000 sq miles).

The population of Sudan is predominantly Muslim and the country’s official languages are Arabic and English.

Even before the war started, Sudan was one the poorest countries in the world. Its 46 million people were in 2022 living on an average annual income of $750 (£600) a head.

The conflict has made things much worse. Last year, Sudan’s finance minister said state revenues had shrunk by 80%.

Who is fighting who in Sudan?

After the 2021 coup, a council of generals ran Sudan, led by the two military men at the centre of this dispute:

- Gen Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the head of the armed forces and in effect the country’s president

- And his deputy and leader of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), Gen Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as “Hemedti”.

They disagreed on the direction the country was going in and the proposed move towards civilian rule.

The main sticking points were plans to include the 100,000-strong RSF into the army, and who would then lead the new force.

The suspicions were that both generals wanted to hang on to their positions of power, unwilling to lose wealth and influence.

What are the Rapid Support Forces?

The RSF was formed in 2013 and has its origins in the notorious Janjaweed militia that brutally fought rebels in Darfur, where they were accused of ethnic cleansing against the region’s non-Arabic population.

Since then, Gen Dagalo has built a powerful force that has intervened in conflicts in Yemen and Libya. He has also developed economic interests including controlling some of Sudan’s gold mines.

Before the current conflict erupted, the RSF had been accused of human rights abuses, including the massacre of more than 120 protesters in June 2019.

Such a strong force outside the army has been seen as a source of instability in the country.

Why did the fighting start?

Shooting between the two sides began on 15 April 2023 following days of tension as members of the RSF were redeployed around the country in a move that the army saw as a threat.

There had been some hope that talks could resolve the situation but these never happened.

It is disputed who fired the first shot but the fighting swiftly escalated in different parts of the country.

Why is the military in charge of Sudan?

The civil war is the latest episode in bouts of tension that followed the 2019 ousting of long-serving President Omar al-Bashir, who came to power in a coup in 1989.

There were huge street protests calling for an end to his near-three decade rule and the army mounted a coup to get rid of him.

But civilians continued to campaign for the introduction of democracy.

A joint military-civilian government was then established but that was overthrown in another coup in October 2021, when Gen Burhan took over.

But then the rivalry between Gen Burhan and Gen Dagalo intensified.

A framework deal to put power back in the hands of civilians was agreed in December 2022 but talks to finalise the details failed.

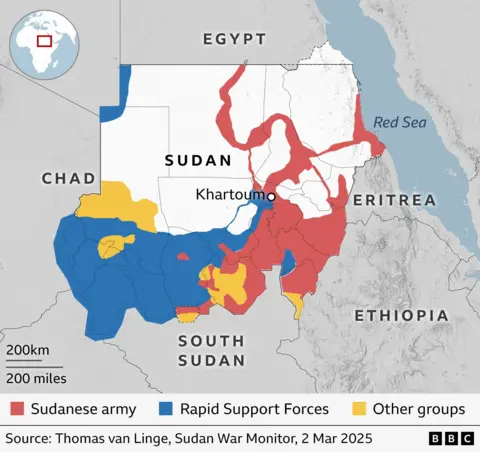

Who controls which parts of the country?

When it began, the conflict appeared to be around the control of key installations.

However, much of it is now happening in urban areas and civilians have become unwitting victims.

The RSF captured Darfur, parts of Kordofan state and, until recently, had controlled much of the capital.

The military controls most of the north and the east, including the key Red Sea port of Port Sudan.

In early 2024, the army recaptured the centre of Omdurman, one of three cities along the River Nile that form Sudan’s wider capital, Khartoum. It regained control of the state broadcaster there – a symbolic breakthrough for the army.

In recent months the army has also won back near total control of the crucial state of Gezira. Losing it to the RSF in late 2023 had been a huge blow, forcing hundreds of thousands of civilians to flee its main city of Wad Madani, which had become a hub for humanitarian services and a refuge for those who had escaped conflict in other parts of the country.

El-Fasher is the last major urban centre in Darfur that is still held by the army. The RSF has laid siege to the city, causing hundreds of casualties, overwhelming hospitals and blocking food supplies.

Attention is now on the army’s offensive on central Khartoum, the area that includes most of the government ministries and financial institutions. Winning back the presidential palace is a symbolic victory – because the palace has great historic and political significance.

How have civilians been impacted by the war?

Where have allegations of genocide come from?

In 2023, the BBC saw fresh evidence of ethnic cleansing in Darfur, most of which has been blamed on militias that are part of – or affiliated with – the RSF.

A report from campaign group Human Rights Watch last year said ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity had been committed against darker-skinned Massalit and non-Arab communities in the region by the paramilitary forces and its Arab allies.

The UK, UN, US and a number of other entities have said civilians in the state are being targeted because of their identity.

Rape is being used to perpetrate ethnic cleansing, says the UN, with fighters taunting non-Arab women during sex attacks with racist slurs and saying they will force them to have “Arab babies”.

UN genocide expert Alice Wairimu Nderitu told the BBC Darfur was facing a growing risk of genocide as the world’s attention remained focused on conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza.

The current violence has erupted out of a long history of tensions over resources between non-Arab farming communities and Arab pastoralist communities.

The RSF emerged from the Janjaweed militia, which was accused of genocide and ethnic cleansing against non-Arab communities in Darfur in 2003, after rebels took up arms, accusing the government of ignoring the region.

The RSF denies responsibility for recent ethnic cleansing in Darfur, saying it is not involved in what it describes as a “tribal conflict”.

How has the world responded to the war?

The UN and other major humanitarian groups have issued several dire warnings about the situation in Sudan, accusing the international community of “forgetting” the African country.

For instance, International Crisis Group has called diplomatic efforts to end the war “lacklustre”, while Amnesty International labelled the world’s response “woefully inadequate”.

Some international bodies have allocated funding to Sudan since the war started. Last year, French President Emmanuel Macron announced a €2bn ($2.1bn; £1.7bn) aid pledge from the international community.

Foreign countries have also attempted to organise negotiations between the army and RSF. There have been several rounds of peace talks in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain – but all have failed.

Last month, Kenya angered Sudanese officials by hosting the RSF and allies where they officially launched plans form a rival government in Sudan. In retaliation, Sudan stopped all imports from Kenya including tea, food and pharmaceutical products.

The African Union and UN have a shared priority – to establish a ceasefire and bring the army and the RSF together.

BBC News deputy Africa editor Anne Soy reports that both sides, especially the army, have shown an unwillingness to work towards these goals.

Last May, the US’s request that the army return to peace talks was denied in firm terms.

Are other countries involved in the war?

According to Reuters news agency, UN experts say the RSF has been backed by neighbouring African states including Chad, Libya and South Sudan throughout the war.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has been accused of arming the RSF, but the Gulf nation has denied any involvement.

Last year, both the UK and the US singled out the UAE in separate appeals for outside countries to stop backing Sudan’s warring parties.

There are also reports that Iranian-made armed drones have helped the army regain territory around Khartoum.